Welcome to Galicia, where the legend of Santiago was born. This northwesternmost corner of the Spanish Peninsula bears little resemblance to the type of landscape that typically comes to mind when thinking about Spain. It is wet, and very green, and the mountains that surround it have for centuries kept it isolated from the rest of the country.

The language here is Gallego and although it has been distilled into one teachable form, you are more likely to get an earful of a more rustic, ancient, and totally incomprehensible version as you pass from one village to another. Village is perhaps too generous of a word, hamlet would be better suited… or perhaps just ‘place’ as so many collections of more than one building are often called here.

For centuries the land here has been fought over by invaders, but the Galicians did not defend it with quite the same gusto as their Basque counterparts and as a result they have spent most of recorded history an occupied nation. Perhaps this is the reason that Galicians have a reputation for being introverted, or guarded, or skeptical, and above all non-committal. Ask a Galician on a staircase the saying goes, and he will be unable to tell you which direction he is heading.

You are likely to find Celtic symbols carved into the stone of a home, or a church. Common also are witches, both the good kind and the bad kind. Hearty soups, a darker bread with a heavier crust, and a strong liqueur (the by-product of the local wine production) are a part of every meal.

The terrain will change as you get closer to Santiago. Mountains shrink as you head west, but they become more frequent and by the time you reach the Apostle you will find precious little flat ground.

O Cebreiro has grown from a small and ancient village of dairy farmers into a small and ancient village of large scale tourism. With luck you will arrive in a shroud of fog and leave with an abundance of sunshine; both suit this village well.

It has played an important role throughout the history of the camino. It was the parish priest, Father Elías Valiña Sampedro, who is most responsible for the resurgence of the camino. It was he that first painted the yellow arrows, and the tales that surrounded him doing so are the stuff of legend. Once, in 1982, he and his white Fiat van parked along a trail in the Pyrenees. It was a time when Basque separatists were trading blows with the Guardia Civil, and when they came upon him, suspicions were aroused.

He opened the van door to reveal cans of yellow road paint and identified himself as the parish priest of O Cebreiro (a long way from home). When asked what he was doing his answer was as simple as it was prophetic: “I am preparing a great invasion!” It was he that orchestrated the installation of the granite hitos as well. His death in 1989 meant that he only got to see the trickling start of his invasion.

The parish church is also the setting for a miracle. According to legend, The Holy Grail was hidden there and in the 14th century produced a miracle that was certified by Pope Innocent VIII. A peasant from a local village braved the hike up to O Cebreiro during a dangerous snowstorm to hear mass. The priest chastised him for endangering his life for a bit of bread and wine. At that the bread and wine turned into flesh and blood, cementing the reputation of this small hamlet.

Santa María and the Holy Miracle are celebrated on the 8th and 9th of September.

From the top, it is mostly downhill, though there remain a few brief climbs, all of the way to Triacastela.

Accommodation in O Cebreiro.

| Albergue de Peregrinos O Cebreiro 10€ 104 |

|

| Albergue Casa Campelo 15€ 10 |

Accommodation in Linares.

| Albergue Linar do Rei 14€ 20 Booking.com |

|

Accommodation in Alto do Poio.

| Albergue Bar Puerto 6€ 16 |

|

Small shop inside the albergue. The village is quite small, only 40 people. Three of the families make their living producing Queixo de Cebreiro, which can be sampled at the bar in the albergue.

Accommodation in Fonfría.

| Albergue A Reboleira - Casa Nuñez 14€ 50 Booking.com |

|

Congratulate yourself on a job well done, the pass into Galicia has been overcome and from here on out the mountains soften in severity.

Triacastela is full of choices: where to eat, where to shop, where to sleep, and even how to leave town.

Accommodation in Triacastela.

| Albergue de Peregrinos Aitzenea 10€ 38 |

|

At the end of town when leaving Triacastela you arrive at a fork in the road, presenting two distinct ways to Sarria. Distances shown are from Triacastela, through Aguiada to Sarria.

Beyond Samos, the camino once again splits, allowing you to rejoin the Calvor and San Xil route in Aguiada. This is the preferred route as it spends the least amount of time along the roadside. Alternatively, you can stay on the road from Samos all the way to Sarria. A third option is to go to Samos, and shortly after turn north to join the other route near Aguiada (distances on next page, after Samos).

via the Monastery at Samos - 25.1 km via aguiada or 21.3 km along road

At the end of town, turn left to follow the road to the Monastery at Samos (all services). The way is generally through small hamlets along country lanes.

via Calvor and San Xil - 18.2 km

At the end of town turn right. Cross the main road to follow a smaller road. The way is generally through small hamlets along country lanes.

via Calvor and San Xil - 18.2 km

At the end of town turn right. Cross the main road to follow a smaller road. The way is generally through small hamlets along country lanes.

You will notice very quickly, through both smell and sight, that dairy cows are the primary trade. The light brown color gives them their name, the Rubia Gallega; though you will also see an imported imposter, the Dutch Holstein.

Between here and San Xil you will pass a large fountain with a large scallop shell with a lot of graffiti and algae. Beyond that by two more kilometers is the Alto de Riocabo. You will also pass through San Xil de Carballo, with no services.

Accommodation in En balsa.

| Albergue El Beso 13€ 16 Booking.com |

|

You will not enter the village of Montán, but rather pass along the edge. While there is no fixed bar, there is a small picnic area with an on-again-off-again vending machine.

You will pass through Fontearcuda and Furela, no services.

The camino does not go through Calvor, but rather passes near its Iglesia de San Estevo y San Pablo. To get to the church, turn left for a short detour once you leave Pintín. The church itself is nothing spectacular, but the site has been home to one building or another since two monks from Samos founded a church here in the 8th century. Also the view towards Samos is worth the detour.

Accommodation in Calvor.

| Albergue de Hospital de Calvor 10€ 22 |

|

Accommodation in San Cristovo do Real.

| Casa Forte de Lusío 10€ 60 |

Pass several villages with no services: Lastres, Freituxe, and San Martiño do Real.

via the Monastery at Samos - 25.1 km via aguiada or 21.3 km along road

At the end of town, turn left to follow the road to the Monastery at Samos (all services). The way is generally through small hamlets along country lanes.

It is difficult to separate Samos from the monastery that dominates this small village. The monastery albergue here is reminiscent of the old albergue in Roncesvalles; one long vaulted space full of hobbling pilgrims, snoring, and laughter. I cannot recommend the experience enough.

Opposite the gas station is the Rúa do Salvador. At the end of this road are a wonderful shaded park and one of the oldest surviving buildings on the camino, the 11th century Capilla del Ciprés.

Pass Foxos, and in Teiguín the camino splits again.

It is possible to stay on the road all the way to Sarria, but the connection to Aguiada is recommended. Along the road to Sarria is 8.8km, via Aguiada 12.6km

Accommodation in Samos.

| Albergue de Peregrinos Monasterio de Samos Donativo€ 70 |

|

| Casa Rural Casas de Outeiro Booking.com |

|

In the small village of O Vao (bar) the camino splits again. This guide follows the path which rejoins the Camino in Aguiada. The alternative to this is to follow the road, which is a more dangerous and less scenic option that is poorly signed. Along the road to Sarria is 8.8km, via Aguiada 12.6km

The remainder of the camino to Sarria is along the footpath adjacent to the road.

Vigo de Sarria

Both Routes rejoin in Vigo de Sarria

Sarria now holds the record for the most albergues in one town. Don’t be alarmed by the swell of pilgrims that appear overnight once you reach this point; the closest city to the minimum 100km point set by the church to be eligible to receive the Compostela Certificate. The effect can be dramatic during the high season and if you have been on the road for a few weeks it can be a challenge to adapt to the change.

If you have arrived early and plan to stay the night, consider the local pool as a place to pamper your feet a bit.

There are plenty of bars and restaurants along the Rúa Maior, where the bulk of the albergues are centered. To get to the grocery shopping though, you have to make your way to the main road where options abound.

The Rúa Maior evolved as a market street during the Middle Ages, due primarily to the pilgrim traffic; and this hasn’t changed. As you walk through town take a moment to admire the well-preserved coats of arms on several of the houses that line the street.

The Iglesia de Santa Maria is an unspectacular example of modern church building, but it does sit atop its 12th century predecessor. The Iglesia de San Salvador is recently restored and is located at the top of the Rúa Maior. Beyond it are the Convento de la Magdalena and the remains of the old Castle. The convent has roots in the 12th century and currently operates as a hospice and a primary school. The Castle is more recent, from the 15th century, and like most castles in Galicia, it is in poor shape. Only one tower remains, the rest was destroyed during the Irmandiña uprisings of 1467 (see below). It was rebuilt, but those efforts also fell into ruin. The remnants have been re-used to pave several of Sarria’s sidewalks.

Along the way between Sarria and Portomarin it is common to find beggars and buskers and the occasional scam artist soliciting your support and money and signature. Do your best to avoid becoming ensnared, the best method is to keep on walking. Also, you are advised to get your credential stamped at least twice a day between here and Santiago.

Archeological digs in the area around Sarria have revealed the presence of a considerable pre-Roman settlement. Documentation supporting more recent inhabitations, on the other hand, is hard to come by, and the earliest written records don’t appear until the 6th century.

Whatever existed at that time was destroyed by the Muslim invasion, and the area wasn’t repopulated until around 750. The town was favored by later Kings and it received funding for several building works from Alfonso IX of León. He was its biggest supporter and he died here in 1230 and is buried in the Cathedral in Santiago.

Irmandiña Uprisings: Also known as “The Great Brotherhood War,” The Irmandiño revolts took place in 15th century Galicia against attempts by the regional nobility to maintain their rights over the peasantry and the bourgeoisie (and by a string of bad crops).

The revolts were also part of the larger phenomenon of popular revolts in late medieval Europe caused by the general economic and demographic crises in Europe during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In Galicia it meant the destruction of any type of fortified structure owned by nobility; over 130 castles were destroyed. The success of the Irmandiña revolts was mixed; the nobility fled to Castile where they rounded up reinforcements and returned to exact revenge on the leaders of the Brotherhood, but few of their former estates and strongholds were ever rebuilt.

The camino exits town along the Rúa Maior in the old town and passes the Convento de la Magdalena. Take note that the camino actually turns left BEFORE arriving at the convent. It goes steeply downhill to the road, turns right, and soon crosses the río Celeiro on the Ponte Áspera. It follows along the river, and in the shadow of a super bridge before crossing the train tracks. The first climb of the day (excluding the stairs in Sarria) is ahead and passes through an ancient forest full of gnarly oaks and chestnut trees.

Accommodation in Sarria.

| Albergue A Pedra 14€ 23 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Don Álvaro 15€ 30 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue O Durmiñento 10€ 41 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Casa Peltre 12€ 22 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Monasterio de la Magdalena 12€ 110 Booking.com |

|

| Alma do Camiño 13€ 100 Booking.com |

|

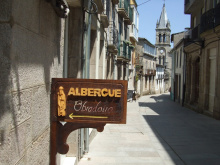

| Albergue Obradoiro 12€ 38 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Puente Ribeira 12€ 30 Booking.com |

|

| PENSIÓN ALBERGUE MATIAS LOCANDA 10€ 40 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Oasis 14€ 27 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue La Casona de Sarria Booking.com |

|

Vilei is often mismarked as Barbadelo on the map and in guidebooks. They are distinct hamlets, less than 1km apart. It has grown into quite a pilgrim stop from the abandoned hamlet it once was. It now counts two albergues and a trinket shop and is a pleasant place to stay if you find Sarria to be overcrowded. It is also the first coffee since Sarria.

Vilei and many of the small hamlets throughout Galicia have always been the agricultural heart of Galicia, working primarily in the dairy industry. Pilgrims come and go, and nothing for them changes much. These clusters of inhabited places are called caserios, and in many cases they number only a few houses and a small chapel.

Accommodation in Vilei.

| Albergue Casa Barbadelo 14€ 40 Booking.com |

|

Barbadelo, small as it is, once housed a monastery in 874. The current church dates from the 12th century and has several quality sculptures, including the animals carved into the north portal. It is 50m off the camino to your left, signed.

A curious place for a medieval market, but that is exactly what this crossing of roads is known and named for.

The camino passes through the hamlets of Leimán, Peruscallo, Cortiñas, Lavandeira, Casal, and Brea. None have any services. The way is more gently rolling hills.

Between here and Morgade you may find, behind a fence on your right-hand side, a rather curious and grumpy ostrich. Ostrich meat is a growing industry in Spain, but this particular fella is the family pet.

As the name implies, Ferreiros was once home to a notable blacksmithing trade. More recently it was another center for small dairy production, and that industry has given way to supporting pilgrims.

Beyond Ferreiros you will encounter the 100km marker. It is the single most vandalized object on the camino, changing from day to day as pilgrims leave their mark. From here on to Santiago the terrain has smoothed out, but do not be deceived. Although the height of the peaks has been reduced, the frequency with which you have to climb the smaller ones has increased.

Accommodation in Ferreiros.

| Albergue Casa Cruceiro 14€ 24 |

|

At the bottom of the hill from Ferreiros, there is a bar and a church/cemetery.

Beyond Mirallos you will encounter the 100km marker. It is the single most vandalized object on the camino, changing from day to day as pilgrims leave their mark. From here on to Santiago the terrain has smoothed out, but do not be deceived. Although the height of the peaks has been reduced, the frequency with which you have to climb the smaller ones has increased.

Not much in town apart from the well-kept albergue/bar Casa do Rego.

You will pass through Rozas and Moimentos, no services.

Accommodation in Pena.

| Albergue Casa do Rego 15€ 6 |

|

Another bar-and-albergue-only kind of town, run by some fellows from Valencia and the most promising place to find paella on the menu.

Accommodation in Mercadoiro.

| Albergue Mercadoiro 12€ 36 |

|

The small shop/cafe here wins the award for flair. It is run by an artist who hand paints camino shells and other souvenir items. Rock and roll sello.

You will pass through Parrocha, no services.

The camino will soon bring you within sight of Portomarín. You will also pass through the town of Vilachá before beginning the rather steep descent into the valley of the río Miño and across the modern bridge to Portomarín.

The camino into town passes over the new bridge. The old bridge spends most of its time submerged beneath the river below but by the end of summer it emerges as the water level drops. Up the stairs and through the small chapel, you are almost into town. It is a bit more uphill still.

Portomarín holds the distinction of being the newest oldest town along the camino. The Portomarín we see today is a transplanted version of the original town that originally settled in the valley below. Most of the town is new construction, but the church and a few smaller buildings were relocated stone by stone. Close inspection of the Iglesia de San Juan shows that the stones were numbered to avoid head scratching later.

The río Miño was dammed in 1956, forming the Embalse de Belasar which sits beneath the bridge. The water level varies by season, and when it is at its lowest it is possible to walk among the piles of stone that were once the original town.

The Iglesia of San Juan (also known as the Iglesia of San Nicolás) is an imposing fortress in the center of town. It is the largest single-nave Romanesque church in Galicia. The Ayuntamiento building in the main square was once the Casa del Conde from the 16th century. The Iglesia de Santa María (also known as La Virgen de las Nieves) is the chapel that you passed under at the top of the stairs going into town; the local people believe that it will protect them from drowning.

Be aware of high-speed traffic as you are required to cross back and forth across the main road.

Portomarín gets its name from ‘porto’ or river crossing, and ‘marín’, a reference to the Sanctuary of St. Marina that was located here in the Middle Ages. It enjoyed its peak of prosperity in the 15th and 16th centuries when several of the Catholic Monarchs slept here. The nearby capital of Lugo, also a Roman settlement, grew at a greater pace and Portomarín was quickly forgotten. As recently as 1919 the town was still not connected by a single road that could accommodate wheeled traffic. That has changed, and the prosperity of the town can now be attributed to the reservoir and the camino.

From the square simply head downhill along the colonnaded street and stick to it until you arrive at the main road. DO NOT keep going straight. Rather turn left and head back in the direction of the bridge into town. Before you get there arrows will direct you onto a different bridge over a small river that feeds the reservoir.

At the end of the bridge are two options: TURN RIGHT.

From here it is a steadily uphill march all the way to Gonzar, passing Toxibo with its hórreo along the way. After passing through a stretch of forest the camino returns to the main road and parallels it on a gravel track. This track crosses back and forth over the main road on several occasions. Be mindful of traffic here, particularly during the morning hours when the area can be thick with fog.

Accommodation in Portomarín.

| Albergue Ultreia Portomarin 14€ 14 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Casa do Marabillas 16€ 6 Booking.com |

|

Hórreo: If you pronounce this word like OREO you are pretty close. Hórreos are commonplace in northern Spain, from the smallest of hamlets to the largest of private estates. They vary in design from region to region and in Galicia they tend to stretch out lengthwise. They function as corn-cribs, with slatted walls that allow for circulation and a foundation designed to prevent rodents from climbing up. They range in length from 2m to 35m.

Gonzar is notable for the number of cows kept there, far more than the human population.

The camino leaves along the road but departs from it quite quickly. You will find that it does this often; the arrows have been placed in a manner which keeps you as far from heavy traffic as possible.

Shortly beyond the village, a mere 50m off the camino to your left, are the remains of the Iron Age castro that gives the town its name. It is seldom visited (there are no signs) but is worth an exploration. It can be found before the point where you meet the main road.

Shortly beyond the village, a mere 50m off the camino to your left, are the remains of the Iron Age castro that gives the town its name. It is seldom visited (there are no signs) but is worth an exploration. It can be found before the point where you meet the main road.

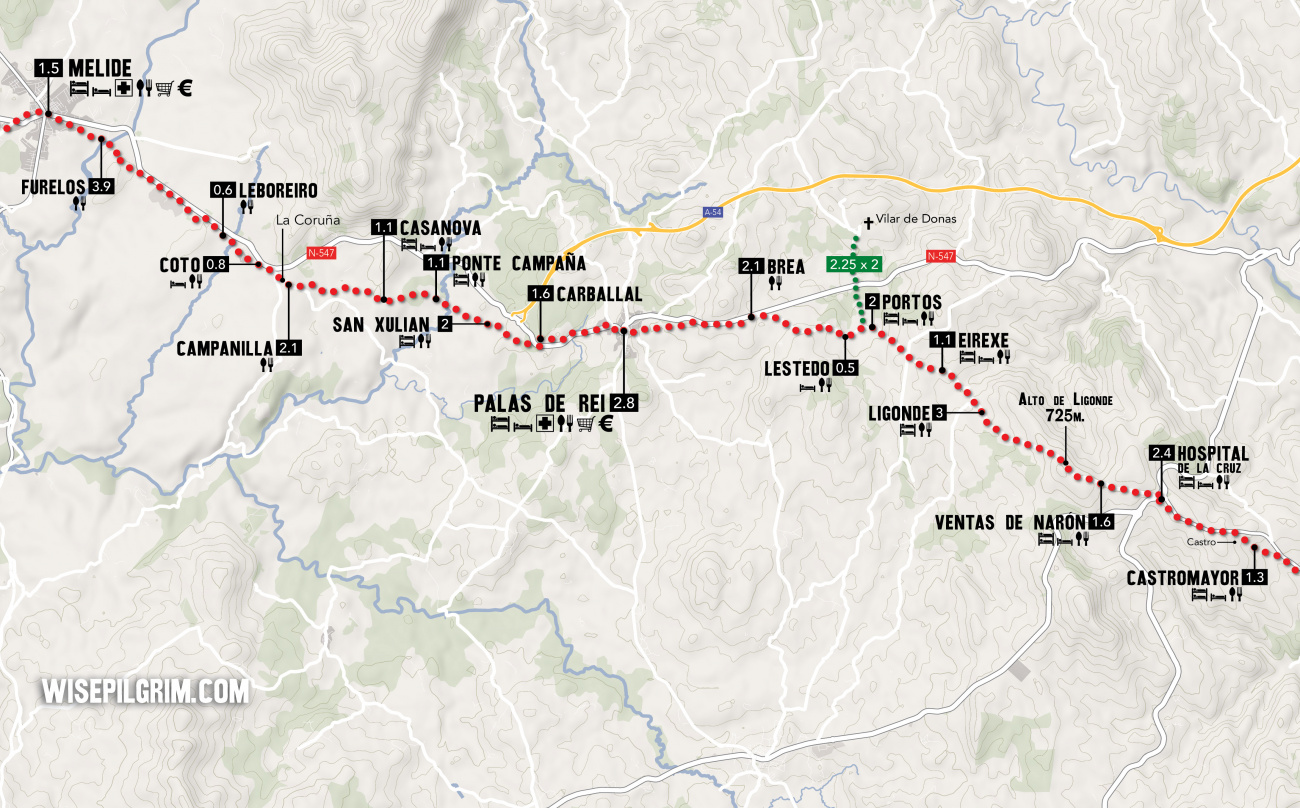

When leaving Hospital de la Cruz it is important to pay close attention to the traffic. The camino crosses a large roundabout, goes over the highway, and then turns left. At this point, you are actually walking along the highway on-ramp, though only for a short distance. It turns right and continues the upward march towards Ventas de Narón.

The bar O Cruceiro opens at 6 am, and there is a wonderful fountain in the picnic area. The small chapel here has a stamp, which is given by its blind caretaker with a bit of help from you.

The land in this area is poor for farming as the soil is rich with quartz and feldspar. The ridge that you are walking towards is the watershed between the río Miño (behind you, which empties into the Atlantic near Guarda) and the río Ulla (ahead of you, and which empties into the Atlantic near Padron). The area is covered thickly with broom.

The year 820 was an important one for Ventas de Naron, and for Christian Spain. For Ventas, it was the site of a battle between the Muslim and Christian forces. The Muslim forces aimed to expand their territory to the north and the Christians, led by the Asturian King Alfonso II the chaste, sent them back. For Christian Spain, it was also the year that the bones of our favorite Apostle were rediscovered. Not long after the very same Alfonso would become the first pilgrim (the primitivo), would verify the relics, would build a church to house them, and would set in motion a course of events that would see the remaining Muslim forces defeated.

Accommodation in Ventas de Narón.

| Albergue Casa Molar 10€ 18 |

|

Locals say that the field on your right at the start of town is a pilgrim cemetery. There doesn’t seem to be any commemoration of that fact, or protection of the site either. Whether it is or is not a cemetery seems less important than the insight gained by remembering how dangerous a pilgrimage of this sort could be.

Accommodation in Ligonde.

| Albergue Fuente del Peregrino Donativo€ 7 |

|

Eucalyptus: The Eucalyptus tree, indigenous to Australia, was brought to Galicia in 1865 for the construction trade. It proved to be a poor choice and is now used to produce paper (most of it is shipped to the mills in Portugal). The Galicians have a love/hate relationship with this invasive species and you will find the occasional message of “Eucalyptus Non!” sprayed on buildings. There are no natural controls for the tree, which grows fast, drives out local species (oak and chestnut), and which are extremely flammable during dry seasons.

Accommodation in Eirexe.

| Albergue de Eirexe 10€ 20 |

|

You will pass through A Prebisa and Lameiros, no services.

Detour to Vilar de Donas and La Iglesia de El Salvador

After passing the bar of Portos, turn right along a gravel road. There is a fork at 500m, keep left and continue strait over the N-547. To the church and back is 4.5km.

Guided tours are offered by a local, and in some cases even when the church is otherwise closed. The official hours are:

Winter (November through March): 12-17:30 closed Mondays

Summer (April through October): 11-14 & 16-20 closed Mondays

The church was given to the Order of Santiago under the pretext that Galician members of the order be buried there. The frescoes in the apse depict the parable of the 10 virgins and is in remarkable condition given that it dates from the early 15th century.

You will pass through Os Valos and Mamurria, no services.

‘Brea’ is Gallego for road, and is a very common name for a small village.

From here the camino passes through more forests and nears the road at Rosario.

Along the descent from here you will pass Os Chacotes, a recreational area with a log-cabin style hotel and sports facilities. At the entrance to Palas de Rei is the Iglesia de San Tirso, where a stamp is available. From there it is down a set of stairs into town.

Palas is bisected by a pair of large roads which twist and turn through town. After coming down the staircase, and with the municipal albergue on your left, the road to the right leads to a grocery and back to Portomarin. Straight on to bars and restaurants and albergues and the road out of town.

The origin of the name Palas de Rei, ‘Palace of the King’, is owed to the last Visigothic king to rule Spain. Witiza had a brief reign, from 700-709, and he was only 14 when he was anointed. The family ruled all of the Iberian peninsula from Toledo and it wasn’t until 701 that Witiza came to Galicia, likely to Tui; his migration was prompted by both a Byzantine invasion and the spread of the plague from Constantinople. His reign was short lived but his namesake village here on the camino remains. For the record, he was, in fact, a co-ruler alongside his father, but ‘Palace of the Half King’ lacked a certain flair.

You have now entered eucalyptus territory, and although there are patches of old oak forests to be found this non-indigenous species has taken over the landscape and has become a symbol of Galicia.

Accommodation in Palas de Rei.

| Albergue Os Chacotes 10€ 112 |

|

| Albergue Outeiro 14€ 57 Booking.com |

|

| Hostel O Castelo Booking.com |

|

You have now entered eucalyptus territory, and although there are patches of old oak forests to be found this non-indigenous species has taken over the landscape and has become a symbol of Galicia.

The bar here opens at 7:30.

Saint Julian is one of the favored Saints of the camino and is the patron of hospitallers and hoteliers. The legend that surrounds his calling to the camino is a dark one: As a young noblemen fond of hunting, he receives a prophecy (by a deer no less) that he would kill his own parents. A believer, young Julian decides to put distance between himself and his parents, getting as far away as Portugal. He finds both work and favor from the King and is married to a young widow.

By a most remarkable circumstance of chance, his parents in the meanwhile had set off looking for him only to find his young wife at home alone. The wife, of course, was overjoyed to realize the family connection and immediately welcomed Julian’s parents into the home and went as far as to offer them rest in her bed while she went to church for her prayers. When Julian returns home to find two people in his marital bed, he slays them both in a rage. Of course, it doesn’t take long for him to realize his mistake, to curse that deer, and to begin his own pilgrimage to Rome seeking forgiveness.

That forgiveness would not come easily; the Pope declared that he would have to care for pilgrims along the road to Santiago. He then returned and with his wife set up a hospice to do as the Pope demanded. He got more than forgiveness for his labors and so did his wife, both were canonized. He, of course, is St. Julian and his wife St. Basilisa. All of this makes for great storytelling of course, but the church itself is undecided on the veracity of it. There are several Julians, surprisingly many Basilisa’s, and chances are good that this tale takes the best of each.

Near San Xulain the camino is undergoing a rerouting to accommodate the new highway connecting Santiago with Lugo. Most recently this meant walking across the unfinished highway. Changes are frequent and it is best to follow the detour signage.

Accommodation in San Xulian.

| Albergue O Abrigadoiro 15€ 17 |

|

Pontecampaña is the setting for a bloody battle which was fought between Fernán Ruiz de Castro (on behalf of King Pedro I of Castile) and Pedro’s half-brother Enrique II. It was 1370 and the resulting feud left ‘rivers of blood.’ Of note today are the remains of the ancient granite bridge over the río Pambre.

With several bars and one casa rural, Coto sits along a small stretch of the old road.

Leboreiro is one of the more charming hamlets along this stretch of road. It is sparsely populated but well maintained. The small Romanesque Iglesia de Santa María de las Nieves has a nice tympanum. Also of note is the first cabaceiro, a small woven structure with a thatched roof that serves the same function as an hórreo.

The church is also surrounded by legend. It is a familiar one, retold in similar churches and capillas all across Europe. It is the ‘legend of the Virgin that moves in the night’. It tells of a mysterious spring that emerged suddenly and which glowed at night. In their search for the source of the spring, the villagers unearthed the statue of the Virgin. They built a chapel nearby (the one we see today) and moved the Virgin to it. Every night she moved back, unhappy in her new home. Unhappy that is until a clever sculptor correctly interpreted her move as a desire to be outside, he carved a figure of the Virgen into the tympanum and the statue has remained at the altar ever since.

In addition to the Iglesia de San Juan, with its uncommon crucifix, Furelos has a bridge and a bar. Both are impressive, the former for dating back to the Romans, and the latter for the tortillas.

The village and its pilgrims hospice were under the ownership of the Hospitallers of San Juan in the 12th century. The Iglesia de San Juan is worth visiting for its quite interesting crucifix which depicts Jesus not with his hands outstretched to his sides, but rather with one hand reaching up to the Heavens and the other down to Earth.

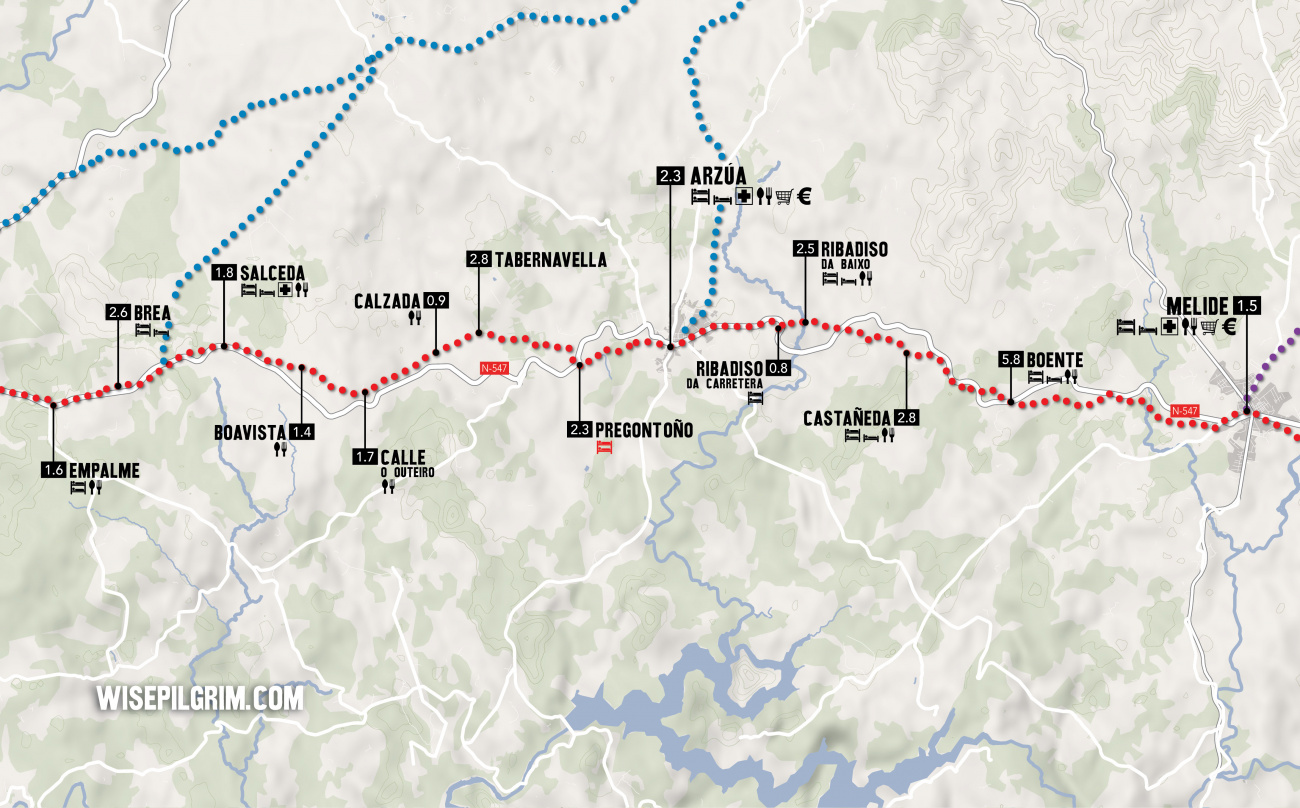

Although it has been on the menu as far back as O Cebreiro, Pulpo (octopus) doesn’t seem to garnish much attention until Melide. Despite its apparent disconnect with the sea, Melide’s thriving Thursday market meant that shipping pulpo was a profitable enterprise. It is served today as it was then: on a wooden plate, garnished only with a healthy drizzle of olive oil and a shake of paprika. It is eaten with a rather crude looking toothpick, alongside heavy Galician bread and a bowl of the local Ribeiro wine.

One of the better places to try it is Pulpería a Garnacha, the last door on your left before you get to the main road in Melide.

The melindre is another of Melide’s favorite foods, and if you like dry and flavorless it can be your favorite too. It resembles a glazed donut and is sold from dozens of identical booths during festivals.

Melide, long the crossroads between territories, is also the meeting point of the various camino routes which come from the north, including the part of the Camino del Norte and the Camino Primitivo. Because of this, and the proximity to Santiago, the road become a great deal more congested.

Melide is an ancient settlement and despite its importance as a natural crossroad since Neolithic times, it has never been protected by a wall. In Medieval times the overwhelming bulk of the town industries were tied to the camino. This is evident today in the way the town is shaped; stretched out lengthwise along the camino road.

The traffic through Melide can be dangerous, particularly on market days when booths line the crowded streets and the arrows through town become difficult to spot. Simply follow along with the main road to the first roundabout. If you have not yet crossed the main road do so at the roundabout, and then cross the road that runs perpendicular to it. Arrows should point you towards a small side street through the old part of town that parallels the main road. There are many other yellow arrows that direct you towards the many albergues in town, they are often attached to adverts or are painted alongside a simple ‘A’. These can be ignored.

Accommodation in Melide.

| Albergue Pereiro 13€ 40 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue O Cruceiro 13€ 88 |

|

| Albergue Melide 14€ 57 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Pension San Antón 15€ 28 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Arraigos 14€ 20 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue O Candil 21*€ 12 Booking.com |

|

The first building in Boente on your left is the Bar de los Alemanes, and this is the best bar in town. Further down the hill, the camino crosses the main road (caution) where two albergues and a few bars are located.

You can get a sello in the Iglesia de Santiago de Boente, and curiously enough the entrance that most pilgrims use leads directly to the sacristy. A collection of hundreds of prayer cards from around the world adorn the walls, and if the priest is not there to stamp your credencial he leaves it out for you to take matters into your own hands.

Walking past the church the camino turns right and descends more. The hills ahead are steep in both directions, take it easy.

It is said that the ovens that produced lime for the construction of the Cathedral were here in Castañeda. Pilgrims carried the raw materials here from Triacastela and swapped it for lime which they carried to Santiago.

It is uphill once more, followed by a steady descent into the valley below, steep at points.

A bar near the river with a large patio for celebrating a successful walk. The river here is quite cold and the perfect place to dip your feet.

The camino to Arzúa begins with a steady walk uphill. By the time you reach the road it levels out and the remaining kilometers are flat into town.

Accommodation in Ribadiso da Baixo.

| Albergue de Ribadiso da Baixo 8€ 70 |

|

There is now an albergue in the upper part of Ribadiso. It is located at the top of the climb and before you get to Arzua.

Accommodation in Ribadiso da Carretera.

| Albergue Milpes 15€ 24 Booking.com |

|

| Miraiso 15€ 10 |

|

Arzúa is a pleasant town with almost enough beds for pilgrims. If you find everything to be full and don’t feel like splurging on one of the many hotels in the area, the Polideportivo (sports hall) is often used to house pilgrims. Between here and O Pedrouzo lie a string of very small Galician hamlets of little note. The locals in these parts enjoy telling you, without the slightest tone of irony or sarcasm, that ‘no hay vacas in Galicia’ (there are no cows in Galicia). Hold that thought in your head while you slosh through a soggy trail on an otherwise sunny day.

Tetilla Cheese: You might have seen this curiously shaped cheese in the shop windows. If you made a connection between the name and the shape you are not mistaken. It was shaped this way by cheese makers in protest to the bishop of Santiago. At the time the Portico de la Gloria (Master Mateo’s famous sculptures at the Cathedrals main entrance) was being finished and the bishop took issue with the odd smile on the prophet Daniels’ face. The clever bishop followed his gaze across the doorway and found that Queen Esther’s bosom was augmented by a cheeky sculptor. Daniel kept his smile, Esther had a reduction, and we got boob-shaped-protest-cheese.

Famous for its cheese, Arzúa hosts an annual (and three day long) Festival of Cheese in March. They have been doing so for 40 years. Apart from this and several other secular celbrations, Arzúa celebrates Corpus Christi, as well as Nuestra Señora del Carmen, who is celebrated on the 16th of July.

The camino leaves Arzúa along a footpath, NOT the road. If you arrived at the main square, walk past the church (with your back to the road) and turn right onto the side street. The terrain is pleasant, a blend of trails and paved roads through small towns and lots of forests. There are a few steep sections but none of any considerable length.

Accommodation in Arzúa.

| Albergue de Arzúa 10€ 46 |

|

| Albergue Ultreia 14€ 38 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Via Lactea 15€ 124 Booking.com |

|

| Casa del Peregrino 10-12€ 14 |

|

Accommodation in Pregontoño.

| Albergue Camiño das Ocas 14€ 30 |

|

Accommodation in Calle - O Outeiro.

| Albergue A Ponte de Ferreiros 15€ 30 |

|

There is a pair of bars in Salceda, and a restaurant (La Esquipa) that is thick with pilgrims every day but Monday when it is closed.

The camino rejoins the road in Salceda, and while it does not walk on the road it does remain quite close. In fact, the camino crosses the road several times between here and Santiago. The speed of traffic, the curves in the road, and the abundance of pilgrims makes this the most dangerous stretch along the camino. Cross carefully and quickly and always under the road when possible.

The camino leaves town to the right of a wedge shaped park next to La Esquipa, not along the road.

Accommodation in Salceda.

| Albergue Turistico de Salceda 17€ 8 Booking.com |

|

CAUTION crossing the road, dangerous intersection.

The camino crosses the main road at the highest point in the road, there is no marked crosswalk and the arrows on the other side of the road are often obscured by parked cars. You may see pilgrims continuing along the road but are advised against following them as the camino returns to the trail when you turn off the road.

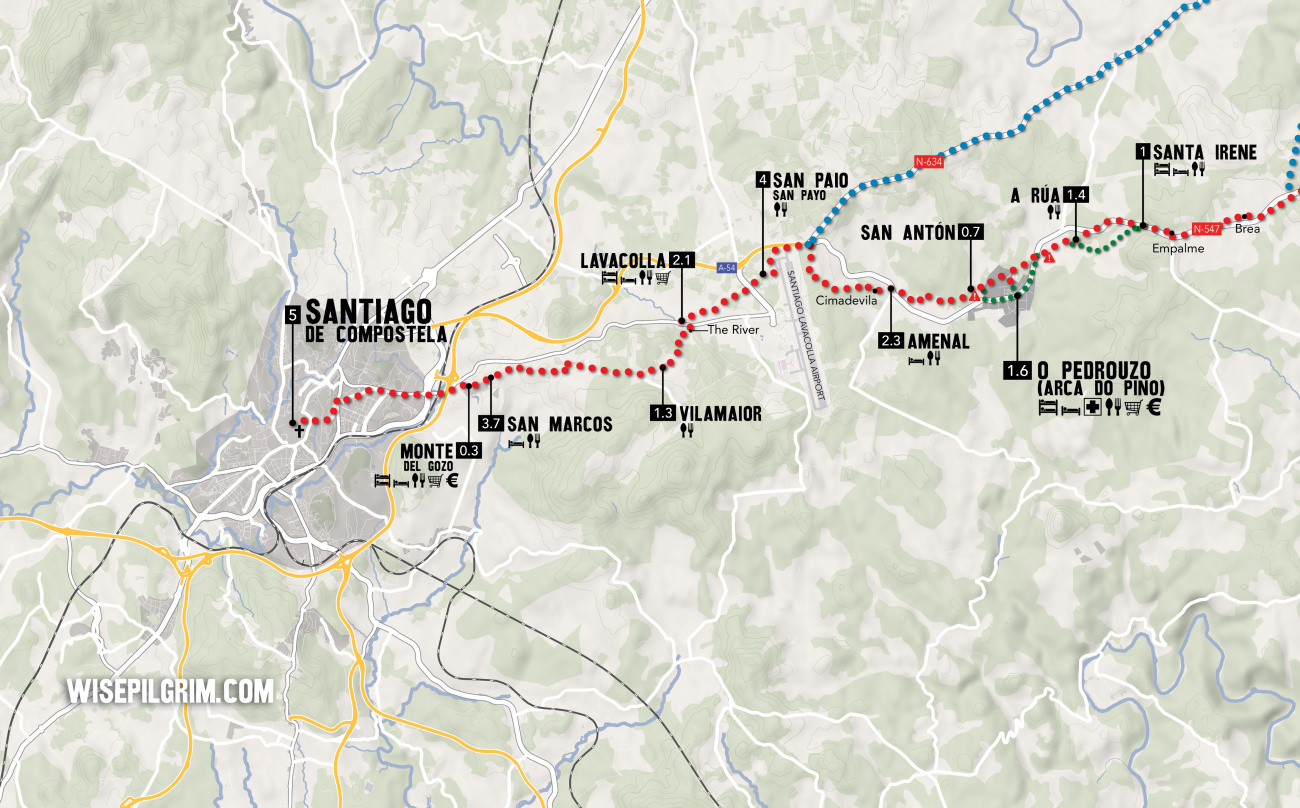

Half way down the hill it splits and arrows indicate that you should either turn left to go under the road or continue straight. Unless you have reason to visit Santa Irene you can keep on straight and avoid the hassle of crossing back over the road. If you continue straight you will arrive at the important part of Santa Irene (the part with the bar).

Accommodation in Empalme.

| Albergue Andaina 12€ 14 |

Accommodation in Santa Irene.

| Albergue Rural Astrar 12€ 20 |

|

Where the camino returns to the road at the start of O Pedrouzo you will find an abundance of arrows and a large map which is nearly worthless. Arrows and dozens of signs advertising various hostels and hotels point in every direction. If you have a reservation, review the map to find the best path, otherwise turn left up the road. If you are not staying the night in O Pedrouzo, cross the road here and continue along the camino.

Unfortunately, there is little to say about this modernized town. When it comes to charm, or monuments, or outrageous legends, it comes up short. During the busier periods along the camino the town feels overrun with pilgrims; most of whom are excited to have finished their penultimate day of walking.

Avoid the temptation of following the main road out of Pedrouzo. There are very few arrows to get you back to the camino and following along the road puts you in very real danger and takes you away from a lovely forest walk. See note below to get back to the camino.

If you spent the night in O Pedrouzo, it is important to find your way back to the camino proper which runs through the forest to the north. To get to it, find the intersection of the main road and Calle de Condello (where the Casa do Concello is located). Continue uphill (north from here) and in a few hundred meters the camino presents itself. Turn left and continue through the forest to Amenal.

The camino between here and Santiago is a mixture of rural and urban settings, some forests and some sprawl. The up and downs that you have been experiencing continue: the elevation gain/loss is +308/-339m, a not insignificant amount.

Accommodation in O Pedrouzo.

| Albergue de Arca do Pino 10€ 120 |

|

| Albergue Porta de Santiago 12€ 54 |

|

| Albergue O Burgo 16€ 14 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Cruceiro de Pedrouzo 12-14€ 94 |

|

| Albergue REM 13€ 40 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Mirador de Pedrouzo 16€ 62 Booking.com |

|

Two bars, one on either side of a dangerous crossing.

The camino crosses the very busy N-547 by passing underneath it. Do not cross over the road.

Leaving the bar behind you climb steeply uphill a short distance. The path soon levels out on a comfortable trail surrounded by eucalyptus trees. The Santiago Airport is very near, and the camino follows a path around the runway.

The written history of San Paio has been lost to the ages, but the church here is dedicated to San Paio (or Payo), the 14 year old saint who was kidnapped by the invading Muslim troops, taken to Sevilla, and ultimately martyred to pieces and tossed into the río Guadalquivir.

The name Lavacolla has one of the most debated origins of all the camino towns. They range from the bland “field at the bottom of the hill” to the more profane “scrub your scrotum.” What is more widely accepted is that pilgrims bathed in this river before entering the Cathedral.

If you walked down the stairs to visit either of the bars at the bottom, turn and walk up the steps towards the Iglesia de Benaval. The camino continues around to the right-hand side and down to cross the road. At the road, cross at the crosswalk and continue along the road and over the famous river (see inset below).

The last hill is ahead, and if you are a stickler for doing things according to tradition you should start running now. It is said that the first of your group to arrive in Monte de Gozo is entitled to be called King. Be advised that there is no prize.

Accommodation in Lavacolla.

| Albergue A Fábrica 23€ 34 Booking.com |

|

Monte de Gozo, or ‘Mount Joy’, was once the first place that pilgrims could get a glimpse of the Cathedral spires. A new stand of trees blocks the view now. It is a large gathering place for pilgrims, who flock to the over-sized monument commemorating the pilgrimage that Pope John Paul II made here in 1993. The modest Capilla de San Marcos has the last stamp and a small kiosk selling cold drinks.

You do not need to enter the complex but for the sake of curiosity, carrying on down the road will take you where you are heading.

Pass the outdoor gallery of a local (and gifted) sculptor of stone and cross the bridge over the highway. It is midway over this bridge that you enter the city of Santiago de Compostela but to keep pilgrims from crossing the road half way across the bridge, the sign indicating such has been moved further into the city.

This outermost barrio of Santiago was once the closest point that pilgrims affected with leprosy were permitted to go.

The walk into Santiago is through the urbanized zone that has grown up around the old town. After passing over the highway bridge the first part of Santiago you walk through is the Barrio San Lazaro; the church here is said to be the limit for pilgrims with leprosy. There is a fairly large intersection to cross where the arrows disappear and are replaced by blue and yellow signs on posts.

At last, you will enter the old town, through the Porta do Camiño, winding gently through the stone paved lanes, through the Plaza Cervantes, under the Bishops residence, and into the Plaza de Obradoiro. Congratulations, and welcome to Santiago de Compostela!

Accommodation in Barrio San Lázaro.

| Residencia de Peregrinos San Lázaro 10€ 80 |

|

Welcome to Santiago! There are a tremendous amount of things to see and things to do in Santiago de Compostela; you are encouraged to stay for at least one full day extra for exploring the web of streets, all of which seem to bring you back to the Cathedral.

Your pilgrim related business is likely to start in front of the cathedral, kilometer zero. A shell and plaque mark the spot in the center of Plaza Obradoiro (see below).

If you are interested in receiving your Compostela, the certificate of completion, you will need to visit the Pilgrim’s Office, which was relocated in 2016 to a bright new building. To get there from the Plaza Obradoiro, face the Parador (the hotel on your left if you are facing the Cathedral) and look for the road that goes downhill to the left. Halfway down you pass the public restroom, and at the next street turn right. The office is at the end of that road and is easy enough to find. Note that there are few arrows indicating the way.

The Cathedral is the single largest attraction to Santiago and for good reason. Both inside and out it presents countless treasures to investigate, too many to list in fact but below are the best.

The Cathedral - Plaza by plaza

1. Plaza de Inmaculada, a.k.a. Azabache: As you enter the city, the first part of the Cathedral that you pass is the Puerta de la Azabachería. This is the entrance that faces the Monastery of San Martín Piñario.

2: Obradoiro: From Azabache you pass under the Palace of the Bishop which is adjoined to the Cathedral and cannot possibly be the sort of palace that affords much peaceful sleeping; the sound of bagpipes welcoming you can be heard from dawn to dusk. The stairway leads directly to the Plaza de Obradoiro and kilometer zero for pilgrims. In the center of the plaza is the last scallop shell and you are likely to find pilgrims taking their shoes off for a photo with it, and the Obradoiro Facade behind them.

This facade is the most majestic and most photographed of the Cathedral and was part of the 18th century building projects that took place in Santiago. The baroque design will keep your eyes moving and the massive amounts of glass allow for the illumination of the Pórtico de la Gloria that lies behind it. That Pórtico was the original front to the church designed by Maestro Mateo 600 years before the new facade.

3. Plaza Platerias: If you continue around the Cathedral you arrive at the Puerta de las Platerías (named for the silver craft that still exists in the shops below it). You will notice that some of the stonework stands out as a different material. These are replacement carvings, the originals were damaged and subsequently moved to the Cathedral Museum; and unfortunately the original composition was forgotten, leaving a somewhat nonsensical layout. In front of the doors are a set of stairs and the Platerías fountain, the usual meeting point for pilgrims commonly referred to as “the horse fountain”.

4: Plaza de Quintana: Continuing up the stairs and around the Cathedral we arrive in the large Plaza de Quintana and the Puerta de Perdón. The actual Holy Door is behind this facade (which is not actually a structural part of the Cathedral, it is more like a highly decorated wall around the Holy Door itself). The carvings here are impressive and depict 24 Saints and prophets.

In medieval times it was common for pilgrims to spend the night in the Cathedral, sleeping on the stone floors and fighting (to the death on a few occasions) for the privilege of sleeping close to their chapel of choice.

The best time to visit is early in the morning before the crowds arrive, when paying a visit to the crypt and hugging the bust of Santiago can be done quietly and with a bit of contemplation.

The botafumeiro, quite possibly the largest thurible in the Catholic Church, is swung across the transept (from north to south) by a group of men called the tiraboleiros. It has only come loose from the ropes twice, and never in modern times. At the time that this book was printed, the tradition of swinging it during the Friday evening mass had been canceled. Inquire at the pilgrim’s office for more information.

The Monastery and Museum of San Martín Piñario

The enormity of this Monastery is difficult to comprehend, but if you pay close attention to this building as you walk around Santiago you will find that you are almost always standing next to it if you are on the north side of the Cathedral. There are three cloisters! The facade of the church often feels like it is somewhere else entirely and is quite curious for the fact that you must descend the staircase to get to the doors, rather than the other way around. The reason for this was a decree by the Archbishop that no building should exceed in elevation that of the Cathedral; the architects did not compromise by redesigning San Martín to be less tall, they simply dug down and started at a lower point.

San Fiz de Solovio

Compared to the two churches above, San Fiz feels like an almost minuscule affair. To find it, make your way to the Mercado de Abastos (Supply Market). San Pelayo (the hermit that rediscovered the bones of Santiago) was praying here when the lights called him. Grand and majestic it is not, but the oldest building site in Santiago it certainly is. The church that exists today is not the original, but excavations have revealed the foundations and necropolis dating to the 6th century.

The Supply Market (Mercado de Abastos)

The produce market is a great place to wander for lunch. Compared to other markets in Spain (like those in Madrid and Barcelona) the Santiago market is a fairly solemn affair. In fact, the architecture appears almost strictly utilitarian and is as Galician as it gets. The vendors make the experience, and even if your Spanish is not up to par, it is worth the visit for a glimpse into the way the locals go about their most ordinary business.

The buildings you see today date from the early 1940’s but replace ones that stood for 300 years. In fact, many of the vendors are second, third, or fifth generation market operators.

Alameda Park

Alameda Park was once the sort of place where the people of Santiago would turn out for elaborate displays of personal wealth and stature; the various paths that cut through and around the park were only to be used by members of a certain class. Nowadays it is far more democratic. The park is the site of a Ferris wheel and feria during the Summer months, an ice skating rink during the Winter holidays, and a massive eucalyptus tree overlooking the Cathedral year round.

The Hidden Pilgrim

Hiding in the shadows cast by the Cathedral, in the Plaza Quintana, is the hidden pilgrim. He is only visible at night and might take a while to discover.

And lastly, there are the many other Monasteries, and while it would be a challenge to visit all of them it is important to realize their construction shaped the city that we see today. Taking the time to walk between them will reveal countless little treasures.

One word of caution regarding accommodation is in order. If you are arriving in the high season, you are advised to make a reservation in advance. There have been several additions to the albergue roster in recent year but the numbers of pilgrims still exceed capacity in the high season.

The Feast day of Saint James is celebrated with a full week of music and dance, with a fireworks display in the Plaza Obradoiro on the evening of the 24th of July. The best views can be had from Obradoiro, or from Alameda park.

Accommodation in Santiago de Compostela.

| Albergue Mundoalbergue 19€ 34 |

|

| Albergue The Last Stamp 19-25€ 62 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Azabache 16-25€ 22 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue La Estrella de Santiago 13-25€ 24 |

|

| KM. 0 20-35€ 54 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue SIXTOS no Caminho 20€ 40 Booking.com |

|

| Albergue Fin del Camino 14€ 110 |

|